NARRATIVE DESIGN BLOG

A little of my musings on the topic of writing in video games.

Skyrim, the Holidays, and the Comfort of Returning

Oftentimes, during the holiday season, I go back and play Skyrim. I return and embark on a sort of in-game pilgrimage taking me from riverwood to whiterun and on occasion, even solitude or the rift. Yet, despite it being a single player experience, it is a journey I do not take alone.

This Blog is also available in video form: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W3YGY55gPwA

Oftentimes, during the holiday season, I go back and play Skyrim. I return and embark on a sort of in-game pilgrimage, taking me from Riverwood to Whiterun and, on occasion, even Solitude or the Rift. Yet, despite it being a single-player experience, it is a journey I do not take alone. According to Steam charts, the game's player base has had a slow but gradual increase from the beginning of October to early December. A decade and change after release, people are still returning in droves. But why? Why, after so many years, is Skyrim still beloved? And why do so many people keep coming back to it during the fall and holiday seasons?

The holidays often makes us think of our childhood. But this does not explain why Skyrim is so nostalgic.

One answer is nostalgia, of course, a desire to return to times that are simpler. Times before the bills and the health insurance and the other nagging complexities of adulthood took up permanent residence in the back of our minds. But in this case, I think there’s a bit more to it than that.

So let’s talk a bit about black magic:

Black Magic

All designers know that there is at least a small amount of “black magic” to game design— the part of the craft where you’re flying by instinct alone.

In one of my older blogs, I tried to understand what made Skyrim so well-loved, by me and others. I hypothesized on some ideas, mostly revolving around the obvious: the soundtrack, the world, the exploration, the ambience, etc. All of those things are certainly reasons that the game holds such a key place in many players’ hearts. But I think there is something else too, an intangible of some sort. Some people refer to this “something” as: “Bethesda Magic” (which is a particular variety of black magic), and avid players of these games will typically know what that refers to even if they can’t put words to it. It’s the game’s secret sauce. And guessing at that secret sauce’s recipe can be a bit of a fool's errand.

But I am nothing if not a fool.

Words of a Fool

A few weeks ago, I came across a video called What’s on the edge of Skyrim? by one of my favorite game design adjacent YouTubers, Any Austin. One of the reasons I enjoy watching him is that he sees games differently than textbooks, journalists, and even designers do. He has an innate ability for sussing out the aforementioned black magic in games.

Liminal Space Game: POOLS

In this video, he makes many interesting points relevant to level, game, and narrative design. He talks about the importance of quiet and empty space in game worlds, the places between the game’s design. The blank spots sandwiched in the middle of quests and POIs and the liminal beauty they often hold. This sort of thing has actually become a popular topic of pop culture discussion under the concept of liminal spaces, though the concept has long predated the term. And, if I may digress further, it strikes me as similar to Pixar’s “emotional contrast” principles in telling stories, except here it’s more of a “spatial contrast,” a common level-design and architectural technique applied at a “world design” scale.

Yet there was a section later in the video that really struck me. And I’m going to take the time and write the whole thing out just because I think there is so much to be learned from it.

Thumbnail from quoted video.

“In places where it’s really snowy and the music hits just right, it feels just like the holidays to me. I know everyone has a ‘holidays thing,’ some piece of media to consume around that time. And to me, I’m unsure of what it is until I sit back down and play Skyrim.”

“And I don’t even necessarily just mean like cozy or nostalgic. I actually kind of mean like spiritually meaningful, almost religious-ish.”

“A big part of this is just the aesthetic, the music, the northern lights, the snow, the setting, the burning fires, the cozy inns. The melancholy loneliness of it all. Skyrim is silly, video games are silly, but it never stops surprising me how, when I’m not looking, they somehow sneak into my brain and take a seat right next to my biggest feelings.”

“And it always kinda happens without me knowing, which is a way that I think games are super different from other forms of art, where you’re always kind of aware of how they’re affecting you right when they are.”

Those paragraphs led me to a sort of AHA moment. (I dropped everything I was doing to write this). I’ve watched long, meandering video essays about Skyrim and read countless articles, too, but there always seemed to be a piece of the puzzle left out. Yet, it was this little quote that struck the right match and finally gave me an answer as to what that “Black magic” was.

Get To The Point, Sam.

I’ve teased long enough, so here it is: The reason Skyrim and similar games (Elden Ring, The Witcher, etc.) are so powerful is that they allow you to make memories; they do so in a way that other, more linear games and things like books or movies do not. Certainly, you remember the end of Arthur Morgan, or what happened to Joel, or Kratos and Atreus’ story. But those are prescribed memories. They are given to you. Only when a game truly embraces freedom and throws caution to the wind do you, the player, have the room to make these memories yourself. I still remember my first journey to Bleak Falls Barrow all those years ago, just as vividly as some of the hikes I’ve taken in the real world. And that’s because it was a discovery, a discovery I made and therefore a memory I created in a game, not one the game created for me.

And with self-created memories comes meaning. Therein lies its magic. It is how certain video games sneak in and “take a seat” next to our biggest feelings.

Of course, many of those Skyrim memories, such as the journey to Bleak Falls Barrow or the troll on the way to High Hrothgar, are carefully designed. So, I’m not suggesting that the key to good game design is, in fact, a lack of design. Quite the contrary.

Troll in suit

The trick and maybe the black magic of the thing is to guide the player just enough to allow them room to make the memory themselves while not suffocating them with control.

Total freedom alone isn’t enough either. Sandbox survival games, for example, offer near-complete freedom, but often lack the worldbuilding, simulation and emotional context that makes those moments stick.

But how?

Screenshot from Avowed

Skyrim and Bethesda magic rides that line perfectly and, in all honesty, is probably some witch's cocktail of open world design experience, raw instinct, polish (in the Game feel sense), and potentially some amount of luck. I believe that Avowed also gets this right, sometimes to a greater degree than Skyrim, though it stumbles in other areas (exposition dumping). The point is these moments are often carefully crafted, but they still make the player feel as if they are making a unique memory, and sometimes, the player actually is.

Here is a relevant excerpt from the book Game Feel on this:

“It is in the polish that much of the impression of a physical reality different from our own exists. With that comes the sense of possibility and wonder that attracts so many to games as a medium. In a few minutes spent feeling their way around, players can extrapolate a universe of possible interactions… and, in doing so, can experience a great joy of discovery and learning that is rarely possible in everyday life.”

Why now?

So why the holidays then? I’m not sure I have the perfect answer. People, of course, make memories and meaning in real life. And people especially form lasting memories during times like the holidays, even more so during childhood. Which I think is why people return to games like Skyrim and Minecraft so often during this time of year. Because, unlike real life, where you cannot revisit those moments and see the same smiling face at the dinner table or your old elementary school classroom, in games, you can.

And that’s special. Really special. It is something no other medium or art form can provide, not to the same degree. In a way, as Austin mentions, it’s sort of spiritual. Even early game theorists like Johann Huizinga considered playgrounds sacred places, not unlike churches. And what is a game like Skyrim if not a big digital playground?

In the age of infinite, easily obtainable information, wonder has become increasingly difficult to come by. Skyrim, and games in general, remain a haven for an emotion as rare as gold, and that’s what makes them special. I would encourage you to experience them and create them for others, whenever possible.

Video games are awesome, and talking about them is awesome, and making them is awesome. Thanks for reading, happy holidays. And, if you need me I’ll be in Whiterun.

— Sam

On Technical Writing: From the Desk of the Bureau #1

A blurb about my lessons working on BFAA, specifically in regard to the art of tech writing

Hard to fathom that it’s been over 20 months of work on The Bureau of Fantastical and Arcane Affairs for me. So it feels about high time to do some personal reflection on game writing, game design, and creative direction.

That being said, I’m going to start a series of posts lovingly named: From the Desk of the Bureau: Lessons in Helming My First Game. Expect releases of this, however often I am inclined to write them, or, if people don’t find it insightful, then possibly this is the only one I’ll write. Who knows. Also, as a quick sidenote, this is meant to be more a log of my own experiences. This is not me telling you how to do things, only my experience and what I’ve found insightful.

I’ve learned such a large amount in this time that it’s hard to know where to begin. But this is a blog post and therefore, I am legally obligated to provide some sort of insights, so let's start with Technical Writing.

Art from the game!

WIP of the games enviorment

How important is Tech Writing?

I learned the hard way (pretty quickly) how important technical writing is. A writer’s job, especially on an indie project, is to write dialogue and quests and flavor text and quest logs etc. That, I already knew. But it is also to create Art prompts, technical and design documentation, and more. And that isn’t exclusively to writers but also applies to leads, programmers, directors, artists, basically everyone. It’s a huge time suck when you’re doing it, but doing this correctly up front is going to save you hours of time down the road.

Technical writing is often also thought to be exclusively used in GDDs or other bibles/documentation pieces, but I think it’s a skill you have to use every day (especially when you work remotely). In one-off messages, small notes to team members, scheduling meetings, etc. The better you get at this skill, the more effective your collaboration is going to be.

Things I practice to be good at Tech Writing:

More art from the game!

A few things that I’ve been doing my best to adopt, and I think they’re working:

- Keeping it short, but not too short. Just enough tone so the reader knows I’m not mad, sad, or whatever.

- For feedback, I’ve found the “I like / I wish / What if” framework to be my favorite.

- If the conversation is dragging on or someone keeps DMing me with confusion (almost always confusion I created) I just bite the bullet and schedule a call. (Yeah, I also hate a bunch of calls, but sometimes you gotta pick the lesser evil)

- I always assume people need more info than I think they need in GDDs. Thoroughness goes a long way. Even with that, there is always stuff that slips through the cracks. It's just how it goes.

- Weirdly, I’ve found that sometimes good tech writing isn’t actually writing but drawing. My drawing resembles that of a 4th grader, but often they communicate what three paragraphs couldn’t. Yada yada picture 1000 words etc, and so on.

- Bonus: I try to shorten my meetings by making a quick agenda before them if I remember to. It takes like 15 minutes and almost always saves more than that.

Five Hundred and Sixty Pages Later.

Reflecting on the Journey to My First Beta Read

Reflecting on the Journey to My First Beta Read

Last week I sent my fantasy novel to other people. It's just a Beta read, but for the first time, someone else will look at that screen and read the words I wrote. Someone else will know the story that has only previously lived in the eye of my mind.

I don’t know if it’s good, or great, or terrible yet. But I know that it’s 170,032 words, I know it took me 971 days to get to this point, and I know that getting to this point, a rough draft, in itself is a huge accomplishment.

Since this is a blog about writing, I’d like to share some things I’ve learned so far. TLDR: Writing a book is hard.

Initially, this was supposed to be a neatly organized article, but it turns out I had a lot of thoughts, so it morphed into something more like loose change of ideas, feel free to skim at your leisure!

Outlines, Drafting, & Discovery Writing

When I started writing this book, I cannot emphasize this enough— I had no idea what I was going to write. And therefore, I had no outline and no idea what I was doing. But the only way to actually do something, even writing a book, is to, well, start it. So I accidentally became a discovery writer.

“ But the only way to actually do something, even writing a book, is to, well, start it.”

For the first 50k words or so, I was working with nothing more than vague emotions and ideas. At first, even those were loose, constantly shifting things. But eventually, I landed on three: Wonder, Coziness, and Dread. And I think sticking to those ideas naturally formed a story around them.

This gif has nothing to do with what I'm talking about but it's just a killer line

A lot has been written about the importance of having an outline and the struggles of discovery writing, but I was stubborn enough to learn by experience. Not having an outline probably added at least 250 days to my drafting time and maybe another 100 to my editing. And eventually, I had to make an outline anyway. But on the other hand, it also produced some really interesting things that I wouldn’t have found otherwise.

Was that trade worth it? No. Would I know that if I hadn’t jumped into the fire headfirst? Also no.

Writing to Scenes

I realized I tend to visualize specific scenes and work towards writing them, with the plot naturally forming in the gaps. I’m not sure how common this is, but my instincts tell me it worked.

Interestingly, I think this might be a generational thing. TikTok and Instagram Reels have taken movies and turned them into edits—bite-sized pieces consisting of emotional music and one scene or a few powerful lines from a work. They communicate the feeling and emotion of a 2-hour movie in 30 seconds. As I’m writing this, I’m realizing only now how big of an impact that probably had on me.

Sharing My Book

This was the first time I shared my book in its entirety, but not the first time I shared pieces of it. I wrote essentially word vomit for the first twenty thousand or so words and, maybe foolishly, decided to share that first section with some close friends of mine.

That was certainly a humbling choice. But I also think it’s maybe the best thing I did that first year of writing. Collaboration is the conveyor belt to creativity. Novel writing is an extremely lonely, hard, and isolating journey. But just being able to sit and talk with someone made it so much clearer what points were interesting. It also made it clear how much farther my writing had to go to be actually enjoyable to read.

“Collaboration is the conveyor belt to creativity.”

I rewrote almost every word of what those friends read, but I would do it again. It was a much-needed grounding that made the work I have now much better.

Editing

I completely underestimated this process. You read a lot of people in online forums talking about how much work editing is, and it’s really easy to think, “Oh, well, it’ll be different for me.”

It wasn’t. Not on my first book, anyway. I spent, in terms of hours, probably just as much time editing as I did drafting, and that isn’t even counting rewrites.

Here is a thing I found helpful, though: Reading out loud (and doing character voices). This significantly helped me nail down character voice (as well as narration voice) and was a massive help for me.

Also, I will never undervalue having a team again. I feel like if I had someone in my ear helping me talk through things, editing would have been so much easier.

Writing Made Me a Better Writer

This is the kind of groundbreaking news you come here for. In total, including what I cut, I probably wrote around 250k words for this draft. That’s a ton of words. And when I went back to edit, it was entirely clear which words were close to the 30k mark and which were close to the 250k mark.

“The best way to learn is by doing” is a tired saying, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Consistency & Grit

The only thing I’ve done that compares to writing a novel is exercise. Want to put on muscle? Go to the gym 5x a week for a few years. Want to run a marathon? Get ready to run most days for the next year or so.

Novel writing is an absolute grind; it is a mental battle with yourself to form habits and stay on track. It’s a sacrifice, but similar to lifting weights or running, it’s extremely rewarding.

Grit is passion and perseverance for very long-term goals, and if that idea intrigues you, I recommend you check out Angela Duckworth’s work.

Stop Thinking and Do It

“I read somewhere that a lot of successful people are just dumb enough to try something stupid and just clever enough to figure it out.”

I read somewhere that a lot of successful people are just dumb enough to try something stupid and just clever enough to figure it out. Well, I’ve got the former; now I just need to get the latter.

Overthinking is death. So maybe I take back my earlier point about the outline. Or maybe not. I’ll let you figure that one out.

How do you “end” an open-world game?

The Witcher 3, “Soft” Endings, Ending dissonance, and Epilogues.

The Witcher 3, “Soft” Endings, Ending dissonance, and Epilogues.

I’ve been playing games for a long time, with open-world ones being some of my favorites. Over the past year or so, I’ve begun studying them with more scrutiny than I had before.

In both cases, few things have made me more sad than games (even ones I absolutely adore) that end by loading your last save file or feature messages like this:

It’s a good representation of the problem open-world games face: If there’s more the player wants to do, how do you “end” the story?

I will never forget the first time I encountered this. It left me with a sour, empty feeling deep in my stomach. All the characters I had cared so much for—I couldn’t talk to them again. I couldn’t decompress after our adventures, couldn’t reflect on the struggle. Most importantly, I couldn’t soak in the feeling of being done, of retiring and hanging up my swords, and getting that elusive “happily ever after.” It didn’t feel like I was “finished.”

And yet, The Witcher 3’s base game handled this quite well, with extensive, isolated epilogues depending on your ending with Ciri. They were amazing, but the empty feeling persisted nonetheless.

So what was that feeling?

“Ending dissonance refers to the disconnect between the end of the main story and the player’s desire to continue exploring. ”

Let’s call it: “Ending dissonance,” which refers to the disconnect between the end of the main story and the player’s desire to continue exploring. Dragging your player character through an open world to chase side quests, even when you know the game is over, creates a massive disconnect between player, world, and character. This happens partly because most open world games mash the story’s climax, falling action, and resolution all into one.

There are worse “ending dissonance” offenders. Breath of the Wild and Tears of the Kingdom are perhaps the worst that come to mind. You spend the whole game trying to save Zelda, and eventually, you do. Then, you’re given a single cutscene before the game abruptly throws you back into the world, never to see or talk to Zelda again. Instead, you’re reloaded into a save after the credits roll. This was so jarring that I decided I didn’t want to go back into the world. (Call me a sap, I know.). More than that, this creates an issue where oftentimes a player (me) feels like they can’t finish the game until all the side content is done, messing up the pacing.

And yes, yes, I understand the technical constraints—the world would have to change. Hyrule Castle has to return to earth after you kill Ganon, the blood moon would no longer appear, and so on. In some games, there’s no real solution; at the game's end, the only threat has been dealt with.

But that shouldn’t stop us from figuring out what works and what doesn’t if it is achievable.

“But that shouldn’t stop us from figuring out what works and what doesn’t if it is achievable.”

And let me be clear,I don’t think games or stories need to have a perfect decompression period.

Many of my favorite stories, like Cyberpunk, God of War, and others, don’t.

But when a game executes its ending perfectly in an open world, something truly special happens. Evidently, the team at CD Projekt Red agreed, as they created what I believe to be the most satisfying open-world ending with the Corvo Bianco Vineyard in a later DLC.

Here’s a quick summary: When you finish the DLC’s story, you get a visitor at your vineyard, which, by the way, is an excellent player home (working on a blog about that now). The visitor depends on your romance options and your main story ending.

The result is a small, repeatable conversation while you sit in a lush field overlooking the beautiful rolling hills of Corvo Bianco.

The conversation options aren’t heavy—they don’t advance the plot. It’s just you catching up with someone you love. It’s simple and probably takes no more than a few minutes of your playthrough. It’s not linked to any grander scheme; it’s just a conversation.

Yet, it’s the moment that stuck with me the most from the whole 100+ hour game.

This picture makes me happy-sad

“It’s just a conversation. Yet, it’s the moment that stuck with me the most from the whole 100+ hour game.”

Eventually, after finishing a few more contracts, I went out of my way to bring Geralt back to the Vineyard. Only then, sitting on that hill with a character I cared for, did I log out for the last time, feeling satisfied, knowing that Geralt’s story was over and that he had retired.

That is an extremely rare feeling to have after completing a game, and something about it is just magical.

“A “soft ending” is one you can return to at any point. It’s a pleasant farewell for when the player believes it’s time to call it a day.”

I would call this a “soft ending”—one you can return to at any point. It’s not the moment immediately after the story’s crescendo but a pleasant farewell for when the player believes it’s time to call it a day. It’s organic and a perfect fit for the interactive format and something only games can accomplish. There are other examples, such as Red Dead 2, but I don’t think there’s another that reaches the same peaks as Blood and Wine.

So, what is the secret to an effective “soft ending” in a video game?

Well, reader, I’m glad you asked. If I were the creative director (I’m not—hire me, please) of a massive open-world game, here’s what I would do, and what I think works:

Letting the player decompress.

The crescendo of a story is the most important part, but often, due to limitations of the medium, falling action is the first thing to go.

Creating a “safe zone.”

The player needs a place they can easily return to when they’re ready to wrap up the game.

Bringing back one or a handful of loved NPCs.

Dialogue that isn’t “plot-advancing.”

Deprioritizing the primary narrative.

Soft endings also happen in games like Skyrim, where the main story takes a backseat, and the player decides when to hang it up, they kinda create their own ending. Interestingly, this doesn’t mean the stakes have to be low—Alduin the World-Eater isn’t exactly a minor threat.

Closure > minor plot holes.

Sometimes it isn’t an option.

Is the player on a timer? Is the game DOOM? Has the world ended and then been restored? Does the world end after the credits roll? Do you want to end on an emotional gut punch?

In these cases, you might consider more succinct epilogues like in Cyberpunk or The Witcher.

These are just my thoughts on the matter. If you have other examples I should check out or if you disagree, shoot me a message—I’m always happy to chat.

Thanks for reading :)

Why Skyrim? And What Makes Its World So Special?

Skyrim’s world is incredible, but what exactly makes it so great? Why do I and so many others love it even in 2024?

I was 13 when Skyrim came out, I am now 27. As I write this, it has 28 thousand people playing on Steam. So many years later, I still haven’t played anything quite like it. It has a special magic that no other game has captured in quite the same way. And no, it isn’t nostalgia, at least not completely. But the question is, why? Why are people so completely enthralled by this game?

Well, last night I watched a video that sought to answer that question, and felt that, while it made some interesting points about things I hadn’t considered before, I only partially agreed with it. A good portion of the video focused on how the game hit the right audience at the right time, rather than focusing on what actually made the game so loved for so long.

That’s not a total knock—the video was made by someone who is ultimately not a fan of Skyrim. As a very avid fan of Skyrim, I wanted to add another perspective. It may be one tainted by love and nostalgia, but I think it’s one worth sharing.

“[It’s] less about playing through the game and more about playing in it.”

My favorite line from the video, and I think it's best point, was this: “[It’s] less about playing through the game and more about playing in it.” That’s completely true. I think 95% of Skyrim lovers would tell you the same thing. It isn’t so much about the game mechanics of Skyrim; it’s about the world of Skyrim. But is that enough? Is simply saying that Skyrim’s world is incredible sufficient? I don’t think so. So, I want to delve into why its world is so special, at least in my eyes.

So, let’s discuss its four main elements: Wonder, Ambience, Coziness, and Discovery—WAC’D, if you like acronyms.

Wonder

Wonder is often the most overlooked aspect of world-building, not only in games but beyond. It’s the joy or excitement of your inner child. It’s seeing a mountain and being able to climb it; it’s finding a hidden canyon with the last of the snow elves living within; it’s walking into the cavern of Blackreach for the first time (a tactic Elden Ring borrowed years later). It’s being able to converse with rulers, join a college of mages, or become a master assassin. You can even interact with gods and earn their weapons. These desires are rooted in the DNA of myth since The Odyssey, and myth is at the core of wonder. Tall tales of heroes past are what we have loved for centuries and continue to love now. Skyrim, from top to bottom, doesn’t take itself too seriously. Instead, it fully embraces the unbridled joy of fantasy in every sense of the word. You’re the hero, and you can be whatever kind of hero you want to be. You might be thinking: that’s just player freedom, which, yeah, it is, I think that’s a big part of the wonder “equation”. Of course, this means sacrificing strong linear storytelling, but that’s okay—it’s not that kind of game. If it feels like I’m being vague, it’s because wonder is an intangible thing based on feel. It’s why people still love Harry Potter, despite a million other clones “just” like it. Perhaps one day, I’ll write an entire post about wonder, but for now, I’ll leave it there.

“These desires are rooted in the DNA of myth since The Odyssey, and myth is at the core of wonder.”

Ambience or “Vibes”

Look no further than this YouTube series if you’re wondering the kind of effect the handcrafted aspect has.

Jeremy Soule should receive a lifetime achievement award for his work on this game alone. The impact of the score cannot be understated. It evokes a sense of adventure in a calm way that many other games struggle to achieve. It has a melodic sweetness that makes you recall a place you’ve never been. Coupled with Skyrim’s vistas, it creates a magic that’s hard to describe. The art style and focus on wilderness also contribute to this feeling. Each NPC being someone you can talk to makes it feel much less simulated and much more hand-crafted, as does being to enter every building. There's no sleight of hand in the way its towns are built or populated. Even the inns genuinely feel like breaks from the wilderness—places you want to visit. The more I think about it, the more important the “hand-crafted” feel is. Every quest feels thoughtful and collaborative, rather than something churned out by a conveyor belt of different departments. For more on the games quest design, I recommend this recent GDC talk. The ambience is a standout strength of this game, at least until the battle music kicks in because a mudcrab five miles away heard you.

“It has a melodic sweetness that makes you recall a place you’ve never been.”

Coziness

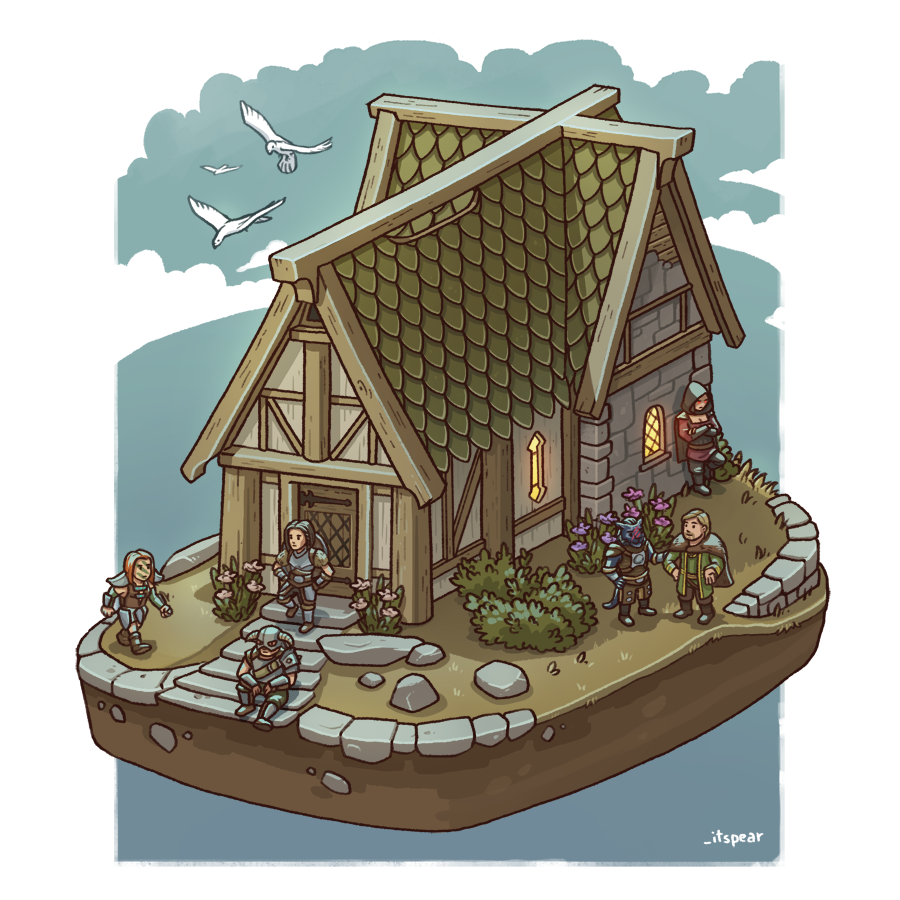

Credit to _itspear for the fun artwork!

Coziness is often overlooked in big-ticket games. They do not allow the player a moment to breathe. For some reason, coziness has been quartered off into its own genre. Because of that, action games and large-scale RPGs often forget about its importance. They ask you to keep going, to check off things on your list, to fight, to run, to profit. They are so occupied with keeping your attention that they forget to just let you wander, to create the moments in between. Where you can enjoy just running around Whiterun, talk to an innkeeper about jobs, or even get your own player home to live in—one that you actually want to decorate. It’s the little things like this that make a game memorable, that make it feel like home.

Discovery

Right now, there is a fairly popular take among those who think of themselves as having finer taste in terms of the games they play: that fast travel shouldn’t exist. I think that’s an unrealistic change, and with the bloat of games, I don’t want to walk across them anyway. Some people only have a few hours to play every day, and expecting them to trek across an open world is a little absurd. And yet, the one exception I would make for this is Skyrim, at least for the first 10-20 hours. You can find some developer interviews about this, but Skyrim’s open world is the perfect balance of “stuff,” meaning it has the ideal gaps between empty space and “discovery moments.” A cave there, a secluded hut with a hint of a story inside, a town where it certainly seems like there’s more than meets the eye. And Skyrim does an excellent job of not “handing you these moments.” Instead, it invites the player to find them for themselves, with a hint of a dirt path climbing upwards, an old ruin you can see from the distance, a far away marker on your minimap, an inconspicuous inn.

The game does not signal these ideas to you in a language that is as obvious as some others; it does not demand you go there. And, often enough, you will find suitable rewards for your exploration, as Skyrim's flexible buildcrafting doesn’t require every item to be a perfect fit for your playstyle. The game invites you to meander but doesn’t force your hand in any way only rewarding you when you do. While often, in other games, this can feel like suffocation by vagueness, Skyrim offers just enough 1-hour mini story hooks and mysteries to keep you engaged. It’s like the bits of cookie dough inside the ice cream—a pleasant pocket of discovery.

And that’s it—those three elements create a world that is both warm and welcoming while also remaining wild and exciting. But there’s something else I want to talk about.

Not everything has to be perfect. In fact, maybe it’s better if it isn’t.

The advantages of imperfection. Skyrim, as many have pointed out, is not a perfect game. Its combat is meh; it’s fairly imbalanced; the cities aren’t Densely-populated; the level scaling can sometimes be annoying, and its writing, while it has some bright spots, isn’t at the level of many of its peers 10+ years later. Please hire dedicated writers, Bethesda—preferably me. But I think if all of those are improved substantially, the world, that feeling of being in Skyrim, would lose something. Every band’s gotta have a lead singer, and for Skyrim, that’s its world. Making the story more compelling and urgent would pull the player away from it. Improving the combat (which modders have done) would completely alter the flow state. Removing level scaling would disincentivize exploration. And, populating the cities would mean a lot of that hand-made feel,, would disappear. Unintentionally or not, Skyrim makes a lot of sacrifices to ensure its world shines as brightly as it can. I don’t think Skyrim succeeds in spite of its flaws, but often because of them.

“Every band’s gotta have a lead singer, and for Skyrim, that’s its world.”

Did you like this post? If so, I am for hire!! If not, well I’m still for hire but my chances are probably not looking great. :/

Dynamic Characters in Video Games.

Recently, I've been having numerous discussions about whether dynamic protagonists work in interactive media/video games.

Recently, I've been having numerous discussions about whether dynamic protagonists work in interactive media/video games.

Now, if you haven't thought about it or don't play games, this might sound a little odd. For static mediums like books, TV, or movies, dynamic protagonists are almost the expectation. You have a character who feels one way about the world, but over the course of whatever you're reading or watching, they change. Pretty simple.

However, for video games, that hasn't been the case, yet. Consider most game protagonists; many are ciphers (characters the player projects themselves onto) like Master Chief, The Dragonborn (Skyrim), or Link. Others with personalities hardly change; think Geralt from The Witcher or Aloy from Horizon.

But why?

There is an extra dimension that needs to be considered when writing a protagonist for something interactive, and that is the player. The best metaphor I've heard is that the player is the driver while the protagonist is riding shotgun. Writing a dynamic character is difficult because you need to make sure the player is:

1. Bought in.

2. Understanding the revelation the character is having.

3. Rooting for the character to change.

Another element is choice; many of the best story-based games aren't linear. You can choose to be the hero or the villain. And even if the choices aren't so black and white, it essentially eliminates the option for character development. How is a character going to have a realization and "become a better person" when the player makes a choice to be evil in most situations?

Of course, I think there are situations where you could make the argument it's been done, like Kratos in God of War 2018 (though part of his change occurs offscreen) or possibly Arthur Morgan, though even then, he only barely changes. And for Kratos to work, the entire game had to be focused on a single relationship.

Maybe as technology gets better, we'll see more people try their hand at dynamic characters, or it will allow it to work in a way that wasn't previously possible.

Effective Barks.

I made it a bit of a mission to learn about barks/callouts in video games. Here's some cool stuff I learned!

I made it a bit of a mission to learn about barks/callouts in video games. Here's some cool stuff I learned!

If you don't know, barks are the lines characters say when they enter specific locations, perform certain actions, or fight types of enemies.

The most (in)famous example is Geralt saying "winds howling" every time there's even a hint of a storm in The Witcher 3. Or the well-known "Arrow to the Knee" line guards make in Skyrim; in fact, basically, any line the guards say in Skyrim.

Those examples are fairly repetitive, but the goal of these lines is to increase the immersion of the player in the world or help them understand a character better through ambient storytelling. This becomes doubly important when you're playing a game where that dialogue is the only kind that exists, like League of Legends by Riot Games.

That leads me to this awesome example I found of the new LoL champion's bark.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifi3XpK8c3E

This taught me a ton.

The amount of lines needed to properly fill out a character like this is impressive; there's 8 minutes, and this is just what MADE THE CUT.

You can tell a character's story through these kinds of callouts/barks alone.

Continuity is important, even without the amazing VA work; each line reads as if it was said by the same character.

I'm working on practicing my own set of barks, but I thought this was a cool example to share!